Thanks to Norma Smith, wife of retired physics professor Stewart Smith, we now have not only the origin story for Einstein begonias, but also the origin story for emigration from Norway to America. Oswald Veblen's ancestors were very much a part of that emigration. Norma mentioned to me the Restauration, which looked at first like a misspelling but upon further research turned out to be the ship that carried the first organized group of immigrants from Norway to the U.S. Their overloaded sloop landed in New York on October 9, 1825, after a three month voyage. That date, October 9, was considered so seminal that it would later be declared Leif Erikson Day, after the first European to lead a voyage to North America, about 500 years before Columbus.

Oswald Veblen's paternal grandparents joined that emigration two decades later, in 1847, leaving their ancestral home in the Valdres valley to then homestead in Wisconsin.

It's interesting to note that that first momentous emigration from Norway to the U.S. was not populated by Lutherans--the dominant religion in Norway--but by Norwegians seeking to escape persecution for their non-Lutheran faith.

The man who organized that first ship full of Norwegians was a character named Cleng Peerson. An

article at NorwayHeritage.com describes the sequence of events that led to this first organized Norwegian emigration to America since Leif Erikson's journey around the year 1000. During the war 1807-1814, some Norwegians who supported Napolean Bonaparte were captured by the British. Influenced by the Quakers they met in prison, they later returned to Norway with new religious leanings. Persecuted in Norway for straying from the Lutheran faith, they sent Cleng Peerson and one other Quaker to explore opportunities in America. Only Peerson survived the trip, and the stories he told upon returning to Norway inspired the voyage of the Restauration the following year.

A pamphlet Norma picked up in Norway, from which this photo is taken, describes the beginning of Norwegian emigration to America as having been motivated by difficult living conditions, in addition to the religious persecution.

Cleng Peerson's role as "father of Norwegian emigration to America" could be seen as heroic, and yet a description of him that the pamphlet quotes is down to earth, even hilarious:

"Heavy work was not his forte, but he never tried to take advantage of others. He worked for the benefit of all, but often in such an impractical manner that few, if any, thanked him for his work."

Sometimes it can be a blessing not to be good at the sorts of things you really best not be doing. Cleng sounds like the sort who was selfless yet was not making himself particularly useful, and so was perfectly suited to leave his community in Norway to scout out possibilities for a better life in America.

Research has revealed several events that intersected with the Veblens' lives.

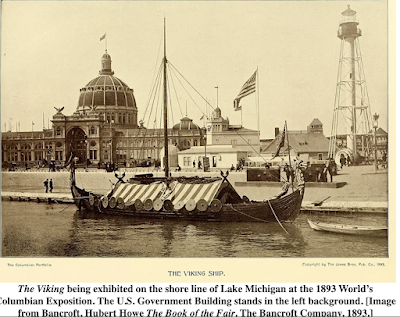

A replica of a Viking ship was built in Norway and sailed to Chicago in time for the 1893 Columbian World's Fair. Oswald and his father Andrew would surely have witnessed its subversive presence, questioning as it did the celebration of Columbus as the first European to discover America. An obituary states that Andrew, a physicist at the University of Iowa, was "twice called as an electrical consultant for the world's fair of 1893."

Andrew's obituary states further that "since his retirement in 1905 (he) devoted nearly all his time to work touching on Norse folk lore, tradition and history, and a family genealogy, for which he had collected material over a period of 25 years. A first edition of the volume was published in 1925."

That publishing date of 1925 was surely timed for Minnesota's 1925 hosting of the Norse-American Centennial, celebrating the Restauration's arrival in NY 100 years prior. Oswald's father lived until 1932, long enough to see both Wisconsin and Minnesota declare Leif Erikson Day a state holiday.