One of the curiosities to be found on the newly exposed walls inside Veblen House are these slats.

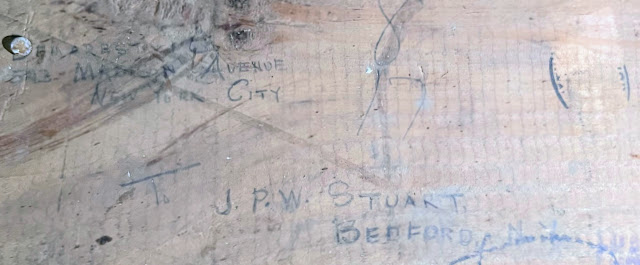

Stacked tightly, one on top of another, they were nailed primarily but not exclusively to the walls that enclose bathrooms. This is the wall between the master bedroom and master bath.and this is the wall between the upstairs hallway and another bathroom. Their function is another mystery to be solved. Soundproofing, perhaps? But suffice it to say that each slat, if I can call them that, looked to us pretty much like all the others.The return address on the crate's top left is 543 Madison Ave, New York City. We couldn't make out the name, though, until I showed it to Clifford Zink. "Demarest," he said without pause. He also pointed out the tiny "&" symbol after Demarest. "Demarest & Cook?", I ventured, before later settling on "Demarest & Co."

Demarest proved to be J.C. Demarest, later fleshed out to James Cleveland Demarest, president and treasurer of an interior decorating firm. His ads appeared in these 1925-26 issues of Arts and Decorations, alongside articles about anything from bathroom adornments to the latest in literature, music, and art. A sophisticated critique of Carl Sandburg's biography of Lincoln rubbed shoulders with Demarest's conception for a well appointed dining room.

This Nov, 1925 issue had lots for the wealthy to contemplate, admire, and buy. Articles come in quick succession, with "The Hard Brilliance of Earnest Hemmingway" (also Conrad Aiken, Sherwood Anderson) on p. 57, followed by some American triumphalism about skyscrapers in "The New Architecture of a Flamboyant Civilization", "Painted Doors are the Final Distinction for the Handsome Room", and "Great Modern Hotels of America." The magazine captures the world the Whiton-Stuarts seem to have inhabited, at least until the crash of 1929. Beginning around 1900, Whiton-Stuart owned a prosperous real estate company that specialized in high-end properties on Madison Ave. in Manhattan. Society pages tracked the Whiton-Stuart's visits to elite locales and later the seven or so marriages of their son and daughter.Jesse grew up on Park Avenue, and collected photographs later compiled in a book entitled "Views and Maps of Old New York."

Another article in Arts and Decorations featured the home of prominent architect Grosvenor Atterbury, who in 1909 designed sophisticated prefab homes for Forest Hills in Queens. According to wikipedia, "each house was built from approximately 170 standardized precast concrete panels, fabricated off-site and assembled by crane." Whiton-Stuart would have been up on the latest trends in architecture--an engagement that may have led to his experimenting with the prefab construction now fully on display at Veblen House.