What are Donna Reed and James Stewart looking at in this scene from director Frank Capra's

It's a Wonderful Life? What could elicit such looks of wonder and endearment?

Why, it's their dream home--a major fixer upper that hasn't been lived in for decades. The broken windows are reminiscent of what happened to Veblen House over decades of neglect, as is the love that the main characters George Bailey and especially Mary later apply to fixing it up as the movie progresses. And, as with George's guardian angel, who mingles with humanity seeking to earn his wings, the ways people contribute to the project at Herrontown Woods can make one feel like there are angels in our midst. But there's something else we noticed that the movie's fixer upper has in common with Veblen House:

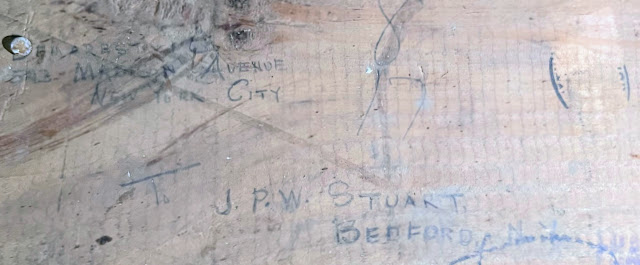

Zoom in and check out the balusters.

I went back through photos of Veblen House from around 2008, when it had already been abandoned for ten years, and found a photo of the outdoor staircase we plan to rebuild.

Was this architectural detail added by the Russian woodworker, said to have customized the house after it was moved to Princeton from Morristown, and where does its style hearken from?

Veblen House is no ordinary house, and Frank Capra was no ordinary movie director. Arriving in America from Italy at the age of six, he became the first in his family to go to college, earning a degree from Caltech in engineering in 1918. The engineering background gave him an advantage over other directors during the transition from silent movies to talkies. A recurring theme in his most well-known movies is the power of an individual to bring out the best in people. It takes a hero--someone endowed with steadfast love, courage, and a deep belief in community and human dignity--to overcome the worst impulses of humanity and mobilize our innate generosity towards one another.

Writing this post, I realized that It's a Wonderful Life is an inverted form of Dickens' Christmas Carol. In Christmas Carol, it is the good will of the community that, along with major interventions by ghosts, ultimately releases the generosity latent behind Scrooge's entrenched greed. In Wonderful Life, it is the main character's devotion to giving and sacrifice that ultimately brings the community together in an outpouring of generosity.

Oswald Veblen's life reads like a Capra movie. Through the first half of the 20th century, he devoted himself to bringing out the best in mathematicians and other scholars, by creating the circumstances--organizational, physical, and financial--within which they would have the freedom and resources to follow their curiosity and do their best work.

Political freedom is another key element in bringing out the best in people, so it's not surprising that Veblen and Capra sought to serve their country. In WWI, while Oswald Veblen was helping the war effort by applying mathematics to the improvement of artillery at Aberdeen Proving Grounds in Maryland, second lieutenant Capra was teaching mathematics to artillerymen in San Francisco.

In WWII, while Veblen was again in the military, coordinating scientific work to improve the accuracy of weaponry, Frank Capra also reenlisted, this time to work for Chief of Staff George C. Marshall. It was Marshall's vision to create films to explain to the troops "why we are fighting, and the principles for which we are fighting." Capra created the series of films called "Why We Fight," which provided the philosophical foundation for the vast collective effort to defeat totalitarianism.

Scientists like Veblen, and artists like Capra--patriots and heroes through the first half of the century--came under suspicion in post-war America, as the fear and repression they had long fought against took hold here at home. Both came under scrutiny by the House Un-American Activities Committee, because of the people they knew. The film industry and cultural mores were also changing, in ways Capra refused to accept and adapt to. He described the new paradigm as "Kill for thrill—shock! Shock! To hell with the good in man, Dredge up his evil—shock! Shock!" Meanwhile, prosperity-fueled development was consuming the rural lands in Princeton that the Veblens loved.

My respect and awe for Capra deepened when I found out he had produced a prescient film in 1958 called "

The Unchained Goddess." About weather, it included a

one minute synopsis of the threat posed by climate change. The movie uses animation reminiscent of his Why We Fight films. Instead of a map showing the U.S. being invaded by Nazis, the new invader is rising sea levels that could ultimately drown large swaths of the nation. America, having defeated totalitarianism abroad, was now threatened by a new invasion, partly self-inflicted, by "unwittingly changing the climate through the waste products of civilization."

Unlike the great collective mobilization that brought victory in WWII, the country has shrugged off Capra's warnings about climate change, choosing instead to fight battles against other enemies, within or beyond our borders, real or illusory. Though It's a Wonderful Life has been described as "a saccharine apotheosis of private life and small town nostalgia," Capra's depiction of people as often their own worst enemy has relevance to the mounting political and environmental crises we now face.

The movie's fixer-upper speaks as well to what we've found at Herrontown Woods, that a spirit of repair, whether of a traumatized nature or a neglected house, can lead to good things.